-40%

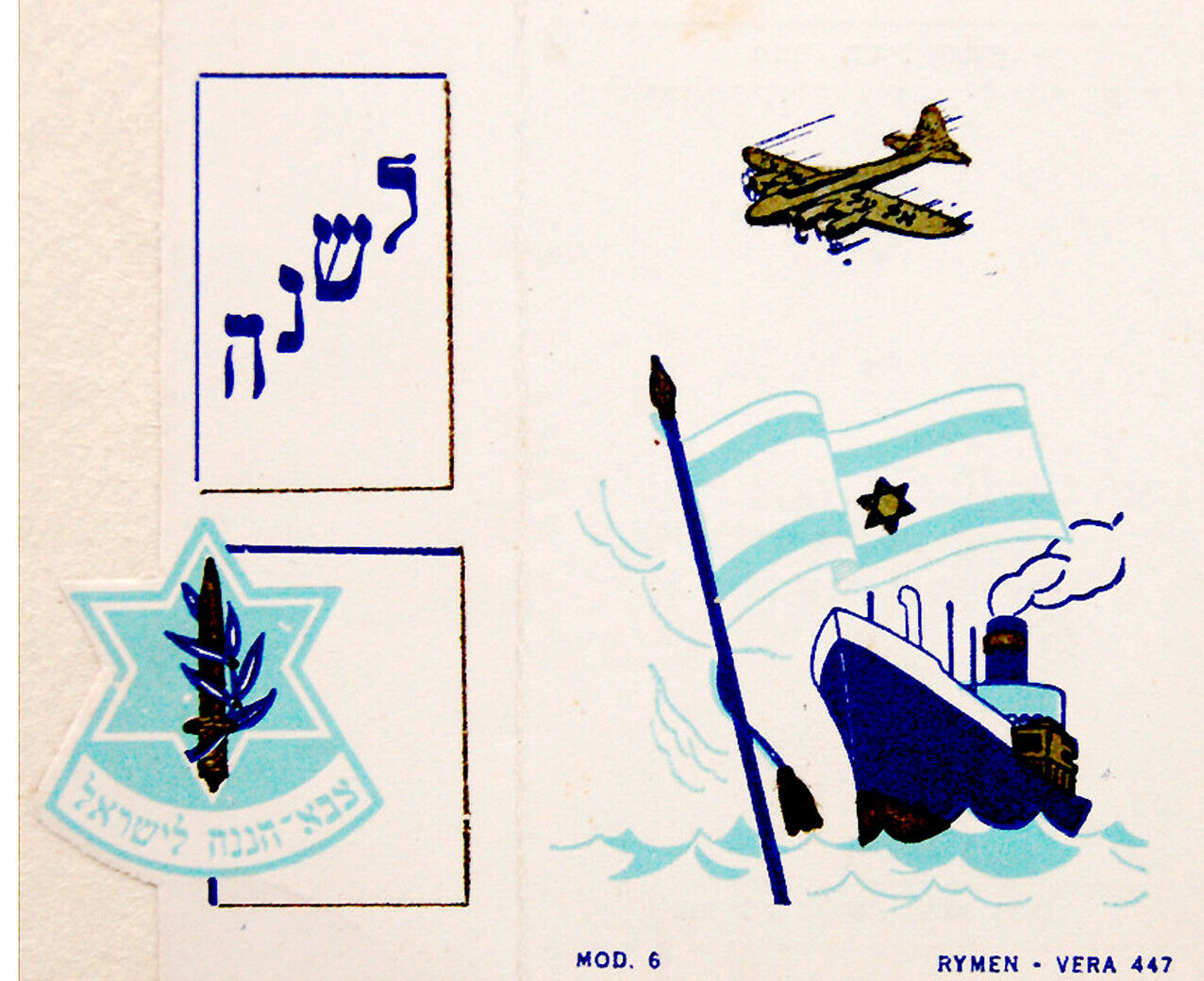

Yiddish SHANA TOVA CARD Jewish CUT OUT Judaica ISRAEL New Year EMBLEM FLAG I.D.F

$ 25.87

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

DESCRIPTION:

Here for sale is an original 1969 vintage SHANA TOVA Spanish Yiddish Hebrew CUT OUT FOLDED greeting card . Depicting the EMBLEM of the STATE OF ISRAEL , The FLAG of ISRAEL , The EMBLEM of IDF and the inevitable PLANE and SHIP to symbolize the IMMIGRATION to ISRAEL. Privately published by a Jewish familly from South America.

VERY RARE . 4 x 2.5" while folded .Around 4 x 6" while opened. Very good condition. .( Pls look at scan for accurate AS IS images )

.Will be sent inside a protective rigid packaging .

AUTHENTICITY

: This is an ORIGINAL vintage 1969 card , NOT a reproduction or a reprint , It comes with life long GUARANTEE for its AUTHENTICITY and ORIGINALITY.

PAYMENTS

:

P

ayment method accepted : Paypal .

SHIPPMENT

:

Shipp worldwide via registered airmail is $ 19

.Will be sent inside a protective rigid packaging .

Will be sent around 5 days after payment .

The widespread custom of sending Jewish New Year's cards dates to the Middle Ages, thus predating by centuries Christian New Year's cards, popular in Europe and the United States only since the 19th century. The custom is first mentioned in the Book of Customs of Rabbi Jacob, son of Moses *Moellin (1360–1427), the spiritual leader of German Jewry in the 14th century (Minhagei Maharil, first ed. Sabionetta, 1556). Based on the familiar talmudic dictum in tractate Rosh ha-Shanah 16b concerning the "setting down" of one's fate in one of the three Heavenly books that are opened on the Jewish New Year, the Maharil and other German rabbis recommended that letters sent during the month of Elul should open with the blessing "May you be inscribed and sealed for a good year." Outside of Germany and Austria, other Jewish communities, such as the Sephardi and Oriental Jews, only adopted this custom in recent generations. The German-Jewish custom reached widespread popularity with the invention – in Vienna, 1869 – of the postal card. The peak period of the illustrated postcard, called in the literature "The Postal Card Craze" (1898–1918), also marks the flourishing of the Jewish New Year's card, produced in three major centers: Germany, Poland, and the U.S. (chiefly in New York). The German cards are frequently illustrated with biblical themes. The makers of Jewish cards in Warsaw, on the other hand, preferred to depict the religious life of East European Jewry in a nostalgic manner. Though the images on their cards were often theatrically staged in a studio with amateur actors, they preserve views and customs lost in the Holocaust. The mass immigration of the Jews from Eastern Europe to the United States in the first decades of the 20th century gave a new boost to the production of the cards. Some depicted America as the new homeland, opening her arms to the new immigrants, others emphasized Zionist ideology and depicted contemporary views of Ereẓ Israel. The Jews of 19th c. Ereẓ Israel ("the old yishuv"), even prior to the invention of the postal card, sent tablets of varying sizes with wishes and images for the New Year, often sent abroad for fundraising purposes. These tablets depicted the "Four Holy Cities" as well as holy sites in and around Jerusalem. A popular biblical motif was the Binding of Isaac, often taking place against the background of the Temple Mount and accompanied by the appropriate prayer for Rosh ha-Shanah. Also common were views of the yeshivot or buildings of the organizations which produced these tablets. In the 1920s and 1930s the cards highlighted the acquisition of the land and the toil on it as well as "secular" views of the proud new pioneers. Not only did this basically religious custom continue and become more popular, but the new cards attest to a burst of creativity and originality on the subject matter as well as in design and the selection of accompanying text. Over the years, since the establishment of the State of Israel, the custom has continued to flourish, with the scenes and wishes on the cards developing as social needs and situations changed. The last two decades of the 20th century have seen a decline in the mailing of New Year's cards in Israel, superseded by phone calls or internet messages. In other countries, especially the U.S., cards with traditional symbols are still commonly sent by mail, more elaborately designed than in the past. Thus, the simple and naïve New Year's card vividly reflects the dramatic changes in the life of the Jewish people over the last generations. BIBLIOGRAPHY: R. Arbel (ed.), Blue and White in Color: Visual Images of Zionism, 1897–1947 (1997); J. Branska, 'Na Dobry Rok badzcie zapisani': Zydowskie karty noworoczne firmy Jehudia (1997); P. Goodman, "Rosh Hashanah Greeting Cards," in: P. Goodman (ed.), The Rosh Hashanah Anthology (1970), 274–79, 356; S. Mintz and S. Sabar, Past Perfect: The Jewish Experience in Early 20th Century Postcards (1998); idem, "Between Poland and Germany: Jewish Religious Practices in Illustrated Postcards of the Early Twentieth Century," in: Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry, 16 (2003), 137–66; idem, "The Custom of Sending Jewish New Year Cards: Its History and Artistic Development," in: Jerusalem Studies in Jewish Folklore, 19–20 (1997/98), 85–110 (Heb.); E. Smith, "Greetings From Faith: Early 20th c. American Jewish New Year Postcards," in: D. Morgan and S.M. Promey (eds.), The Visual Culture of American Religions (2001), 229–48, 350–56; D. Tartakover, Shanah Tovah: 101 Kartisei Berakhah la-Shanah ha-Ḥadashah (Heb., 1978); M. Tzur (ed.), Ba-Shanah ha-Ba'ah: Shanot Tovot min ha-Kibbutz (2001). ***** Rosh Hashanah (Hebrew: ראש השנה, literally "head of the year," Biblical: [ˈɾoʃ haʃːɔˈnɔh], Israeli: [ˈʁoʃ haʃaˈna], Yiddish: [ˈrɔʃəˈʃɔnə]) is a Jewish holiday commonly referred to as the "Jewish New Year." It is observed on the first day of Tishrei, the seventh month of the Hebrew calendar,[1] as ordained in the Torah, in Leviticus 23:24. Rosh Hashanah is the first of the High Holidays or Yamim Noraim ("Days of Awe"), or Asseret Yemei Teshuva (The Ten Days of Repentance) which are days specifically set aside to focus on repentance that conclude with the holiday of Yom Kippur. Rosh Hashanah is the start of the civil year in the Hebrew calendar (one of four "new year" observances that define various legal "years" for different purposes). It is the new year for people, animals, and legal contracts. The Mishnah also sets this day aside as the new year for calculating calendar years and sabbatical (shmita) and jubilee (yovel) years. Rosh Hashanah commemorates the creation of man whereas five days earlier, on 25 of Elul, marks the first day of creation.[2] The Mishnah, the core text of Judaism's oral Torah, contains the first known reference to Rosh Hashanah as the "day of judgment." In the Talmud tractate on Rosh Hashanah it states that three books of account are opened on Rosh Hashanah, wherein the fate of the wicked, the righteous, and those of an intermediate class are recorded. The names of the righteous are immediately inscribed in the book of life, and they are sealed "to live." The middle class are allowed a respite of ten days, until Yom Kippur, to repent and become righteous; the wicked are "blotted out of the book of the living."[3] Rosh Hashanah is observed as a day of rest (Leviticus 23:24) and the activities prohibited on Shabbat are also prohibited on Rosh Hashanah. Rosh Hashanah is characterized by the blowing of the shofar,[4] a trumpet made from a ram's horn, intended to awaken the listener from his or her "slumber" and alert them to the coming judgment.[5] There are a number of additions to the regular Jewish service, most notably an extended repetition of the Amidah prayer for both Shacharit and Mussaf. The traditional Hebrew greeting on Rosh Hashanah is שנה טובה shana tova [ʃaˈna toˈva] for "a good year", or shana tova umetukah for "a good and sweet year." Because Jews are being judged by God for the coming year, a longer greeting translates as "may you be written and sealed for a good year" (ketiva ve-chatima tovah). During the afternoon of the first day the practice of tashlikh is observed, in which prayers are recited near natural flowing water, and one's sins are symbolically cast into the water. Many also have the custom to throw bread or pebbles into the water, to symbolize the "casting off" of sins. Names and origins The term "Rosh Hashanah" does not appear in the Torah. Leviticus 23:24 refers to the festival of the first day of the seventh month as "Zicaron Terua" ("a memorial with the blowing of horns"). Numbers 29:1 calls the festival Yom Terua, ("Day of blowing the horn") and defines the nature of animal sacrifices that were to be performed.[6][7] (In Ezekiel 40:1 there is a general reference to the time of Yom Kippur as the "beginning of the year."[6] but it is not referring specifically to the holiday of Rosh HaShanah.) The Hebrew Bible defines Rosh Hashanah as a one-day observance, and since days in the Hebrew calendar begin at sundown, the beginning of Rosh Hashanah is at sundown at the end of 29 Elul. The rules of the Hebrew calendar are designed such that the first day of Rosh Hashanah will never occur on the first, fourth, or sixth days of the Jewish week[8] (ie Sunday, Wednesday or Friday) Since the time of the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE and the time of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai, normative Jewish law appears to be that Rosh Hashanah is to be celebrated for two days, due to the difficulty of determining the date of the new moon.[6] Nonetheless, there is some evidence that Rosh Hashanah was celebrated on a single day in Israel as late as the thirteenth century CE.[9] Orthodox and Conservative Judaism now generally observe Rosh Hashanah for the first two days of Tishrei, even in Israel where all other Jewish holidays dated from the new moon (except Rosh Hodesh - the New Month, on which Rosh Hashanah falls) last only one day. The two days of Rosh Hashanah are said to constitute "Yoma Arichtah" (Aramaic: "one long day"). The observance of a second day is a later addition and does not follow from the literal reading of Leviticus. In Reconstructionist Judaism and Reform Judaism, some communities only observe the first day of Rosh Hashanah, while others observe two days. Karaite Jews, who do not recognize Jewish oral law and rely solely on Biblical authority, observe only one day on the first of Tishrei, since the second day is not mentioned in the Torah. Laws on the form and use of the shofar and laws related to the religious services during the festival of Rosh Hashanah are described in Rabbinic literature such as the Mishnah that formed the basis of the tractate "Rosh HaShana" in both the Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud. This also contains the most important rules concerning the calendar year.[10] In Jewish liturgy Rosh Hashanah is described as "the day of judgment" (Yom ha-Din) and "the day of remembrance" (Yom ha-Zikkaron). Some midrashic descriptions depict God as sitting upon a throne, while books containing the deeds of all humanity are opened for review, and each person passing in front of Him for evaluation of his or her deeds. Rosh Hashanah occurs 163 days after the first day of Passover (Pesach). In terms of the Gregorian calendar, the earliest date on which Rosh Hashanah can fall is September 5, as happened in 1899 and will happen again in 2013. The latest Rosh Hashanah can occur relative to the Gregorian dates is on October 5, as happened in 1967 and will happen again in 2043. After 2089, the differences between the Hebrew calendar and the Gregorian calendar will result in Rosh Hashanah falling no earlier than September 6. Historical origins In the earliest times the Hebrew year began in autumn with the opening of the economic year. There followed in regular succession the seasons of seed-sowing, growth and ripening of the corn (here meaning any grain) under the influence of the former and the latter rains, harvest and ingathering of the fruits. In harmony with this was the order of the great agricultural festivals, according to the oldest legislation, namely, the feast of unleavened bread at the beginning of the barley harvest, in the month of Abib; the feast of harvest, seven weeks later; and the feast of ingathering at the going out or turn of the year (See Exodus 23:14-17; Deuteronomy 16:1-16). It is likely that the new year was celebrated from ancient times in some special way. The earliest reference to such a custom is, probably, in the account of the vision of Ezekiel (Ezek 40:1). This took place at the beginning of the year, on the tenth day of the month (Tishri). On the same day the beginning of the year of jubilee was to be proclaimed by the blowing of trumpets (Lev 25:9). According to the Septuagint rendering of Ezek 44:20, special sacrifices were to be offered on the first day of the seventh month as well as on the first day of the first month. This first day of the seventh month was appointed by the Law to be "a day of blowing of trumpets". There was to be a holy convocation; no servile work was to be done; and special sacrifices were to be offered (Lev 23:23-25; Num 29:1-6). This day was not expressly called New-Year's Day, but it was evidently so regarded by the Jews at a very early period. Rosh Hashanah will occur on the following days of the Gregorian calendar: Jewish Year 5769: sunset September 29, 2008 - nightfall October 1, 2008 Jewish Year 5770: sunset September 18, 2009 - nightfall September 20, 2009 Jewish Year 5771: sunset September 8, 2010 - nightfall September 10, 2010 Jewish Year 5772: sunset September 28, 2011 - nightfall September 30, 2011 Jewish Year 5773: sunset September 16, 2012 - nightfall September 18, 2012 Religious observance and customs Rosh Hashanah is a day of rest (Leviticus 23:24): with some variations, the activities prohibited on Shabbat are also prohibited on all major Jewish holidays, including Rosh Hashanah. Rosh Hashanah is characterized by the blowing of the shofar,[11] a trumpet made from a ram's horn. Preceding month The Yamim Noraim are preceded by the month of Elul, during which Jews are supposed to begin a self-examination and repentance, a process that culminates in the ten days of the Yamim Noraim known as beginning with Rosh Hashanah and ending with the holiday of Yom Kippur. The shofar is blown in traditional communities every morning for the entire month of Elul, the month preceding Rosh Hashanah. The sound of the shofar is intended to awaken the listener from his or her "slumber" and alert them to the coming judgment.[12] Orthodox and some Conservative Jewish communities do not blow the shofar on Shabbat.[13] In the period leading up to the Yamim Noraim (Hebrew, "days of awe") penitential prayers, called selichot, are recited. Erev Rosh Hashanah The day before Rosh Hashanah is known as Erev Rosh Hashanah in Hebrew. It falls on the 29th day of the Hebrew month of Elul, the day before the 1st of Tishrei. Some communities have the customs to perform Hatarat nedarim - a nullification of vows - after the morning prayer services during the morning of Erev Rosh Hashanah. The mood becomes festive but serious in anticipation of the new year and the synagogue services. Many Orthodox men have the custom to immerse in a mikveh in honor of the coming day. Day of Rosh Hashanah On Rosh Hashanah itself, religious poems, called piyyuttim, are added to the regular services. Special prayer books for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, called the mahzor (plural mahzorim), have developed over the years. Many poems refer to Psalms 81:4: "Blow the shofar on the [first day of the] month, when the [moon] is covered for our holiday". Rosh Hashanah has a number of additions to the regular service, most notably an extended repetition of the Amidah prayer for both Shacharit and Mussaf. The Shofar is blown during Mussaf at several intervals. (In many synagogues, even little children come and hear the Shofar being blown.) Biblical verses are recited at each point. According to the Mishnah, 10 verses (each) are said regarding kingship, remembrance, and the shofar itself, each accompanied by the blowing of the shofar. A variety of piyyutim, medieval penitential prayers, are recited regarding themes of repentance. The Alenu prayer is recited during the repetition of the Mussaf Amidah. There are four different sounds that the Shofar makes: Tekiah (one long sound) Shevarim (3 broken sounds) Teruah (many short, staccato sounds, usually 9) Tekiah Gedolah (a very long sound) During the afternoon of the first day occurs the practice of tashlikh, in which prayers are recited near natural flowing water, and one's sins are symbolically cast into the water. Many also have the custom to throw bread or pebbles into the water, to symbolize the "casting off" of sins. In some communities, if the first day of Rosh Hashanah occurs on Shabbat, tashlikh is postponed until the second day. The traditional service for tashlikh is recited individually and includes the prayer "Who is like unto you, O God...And You will cast all their sins into the depths of the sea", and Biblical passages including Isaiah 11:9 ("They will not injure nor destroy in all My holy mountain, for the earth shall be as full of the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea") and Psalms 118:5-9, 121 and 130, as well as personal prayers. Rosh Hashana Seder and Symbolic Foods Rosh Hashanah meals often include apples and honey, to symbolize a sweet new year. Various other foods with a symbolic meaning may be served, depending on local minhag (custom), such as tongue or other meat from the head of an animal (to symbolize the head of the year). Other symbolic foods are eaten in a special Rosha Hashana Seder, particularly in the Sephardic and Mizrahi communities. Symbolic foods are eaten in a ceremony called the Yehi Rasones or Yehi Ratzones[15][16][17]. Yehi Rason / Ratzon means "May it be Your will", and is the name of the ceremony because the names of the symbolic foods eating have names that are puns in Hebrew or Aramaic. Each pun serves as a desire or prayer that God will fulfill that desire represented by the pun. Foods consumed during the Yehi Rasones vary depending on the community. Some of the symbolic foods eaten are dates, black-eyed beans, leek, spinach and gourd, all of which are mentioned in the Talmud. Pomegranates are used in many traditions: the use of apples and honey is a late medieval Ashkenazi addition, though it is now almost universally accepted. Typically, round challah bread is served, to symbolize the cycle of the year. Gefilte fish and Lekach are commonly served by Ashkenazic Jews on this holiday. On the second night, new fruits are served to warrant inclusion of the shehecheyanu blessing, the saying of which would otherwise be doubtful (as the second day is part of the "long day" mentioned above). In rabbinic literature Philo, in his treatise on the festivals, calls Rosh Hashanah the festival of the sacred moon and feast of the trumpets, and explains the blowing of the trumpets as being a memorial of the giving of the Torah and a reminder of God's benefits to mankind in general ("De Septennario," § 22). The Mishnah, the core text of Judaism's oral Torah, contains the first known reference to the "day of judgment". It says: "Four times in the year the world is judged: On Passover a decree is passed on the produce of the soil; on Shavuot, on the fruits of the trees; on Rosh Hashanah all men pass before Him ("God"); and on the Feast of Tabernacles a decree is passed on the rain of the year. R. Yaakov Kamenetsky explains that in earlier generations it was considered preferable not to reveal that it was a "day of judgment" so as not to mix any other feeling into "the day of the coronation of G-d". In later generations as people lost touch with the significance of the day it was necessary to reveal that it was also "the day of judgment" so that people would approach the holiday with proper awe and respect. (B'Mechitzot Rabbenu) According to rabbinic tradition, the creation of the world completed on 1 Tishrei. The observance of the 1 Tishrei as Rosh Hashanah is based principally on the mention of "zikkaron" (= "memorial day"; Lev 23:24) and the reference of Ezra to the day as one "holy to the Lord" (Neh 8:9) seem to point. The passage in Psalms 81:5 referring to the solemn feast which is held on New Moon Day, when the shofar is sounded, as a day of "mishpat" (judgment) of "the God of Jacob" is taken to indicate the character of Rosh Hashanah . In Jewish thought, Rosh Hashanah is the most important judgment day, on which all the inhabitants of the world pass for judgment before the Creator, as sheep pass for examination before the shepherd. It is written in the Talmud, in the tractate on Rosh Hashanah that three books of account are opened on Rosh Hashanah , wherein the fate of the wicked, the righteous, and those of an intermediate class are recorded. The names of the righteous are immediately inscribed in the book of life, and they are sealed "to live." The middle class are allowed a respite of ten days till Yom Kippur, to repent and become righteous ; the wicked are "blotted out of the book of the living" (Psalms 69:29). The zodiac sign of the balance for Tishrei is claimed to indicate the scales of judgment, balancing the meritorious against the wicked acts of the person judged. The taking of an annual inventory of accounts on Rosh Hashanah is adduced by Rabbi Nahman ben Isaac from the passage in Deut 11:12, which says that the care of God is directed from "the beginning of the year even unto the end of the year". 1 Tishrei was considered as the beginning of Creation. It is said in the Talmud that on Rosh Hashanah the means of sustenance of every person are apportioned for the ensuing year; so also are his destined losses. The Zohar, a medieval work of Kabbalah, lays stress on the universal observance of two days, and states that the two passages in Job 1:6 and Job 2:1, "when the sons of God came to present themselves before the Lord," refer to the first and second days of Rosh Hashanah , observed by the Heavenly Court before the Almighty. (Zohar, Pinchas, p. 231a) Traditional Rosh Hashanah greetings Shana Tova (pronounced [ʃaˈna toˈva]) is the traditional greeting on Rosh Hashanah which in Hebrew means "A Good Year." Shana Tova Umetukah is Hebrew for "A Good and Sweet Year." Ketiva ve-chatima tovah is a longer greeting on Rosh Hashanah. The Hebrew translates as "May You Be Written and Sealed for a Good Year."Rosh Hashanah cards, those annual holiday greetings sent each September to friends and family, are pretty much obsolete. Get The Times of Israel's Daily Edition by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign up!But until recently, sending greeting cards were as elemental to Rosh Hashanah preparations as hearing the call of the shofar or eating honey cake. In fact, people sent New Year’s greeting cards for more than a century, said Israel Museum curator Rachel Sarfati, reflecting on “Each Year Anew: A Century of Shanah Tovah Cards,” a new exhibit curated on the subject. “It was a time when this was the form of communication between people,” said Sarfati. “Our collection ends with the other forms of communication that exist now.” The exhibit is based on the Haim Stayer collection of greeting cards, which tripled the museum’s original collection to more than 3,000 cards, said Sarfati. The museum’s first collection of New Year’s cards was based on what it initially received from the Bezalel National Museum, the art museum that formed the core of the Israel Museum’s original collection. Three-dimensional Shanah Tovah cards, 1910–19. Printed in Germany for the American Jewish market (Courtesy Israel Museum) In its heyday, New Year’s cards offered iconic snapshots of graphic design styles and images that harkened to the relevant moments of the previous year. It was a custom first popularized in Germany, wrote Sarfati in the catalog accompanying the exhibit, where the printing press industry first flourished. The German printing companies also exported cards to the American Jewish market at the turn of the 20th century. Yet the tradition of sending New Year’s greeting cards had its roots in Jewish law, noted Sarfati. Talmudist Yaakov ben Moshe Levi Moelin, also known as Maharil, the Hebrew acronym for “Our Teacher, the Rabbi, Yaakov Levi,” was a leading German rabbinic authority in the 14th century who wrote about sending Rosh Hashanah greetings, wishing one’s friends and loved ones to be inscribed in the book of good life, one of the major themes of the holiday liturgy. Romantic greetings for the New Year, 1928, printed in Germany for Verlag Central Company, Warsaw (Courtesy Israel Museum) It was a custom that ended up being carried into the Old Yishuv, the early community of pre-state Palestine, wrote Sarfati, and eventually was adapted by new immigrants to Israel, even by those who didn’t recognize the ritual from their own home countries. The Israeli printing industry eventually became a leader in the creation of New Year’s cards and calendars, and the business reached an all-time high in the 1950s and 1960s, when vendors would appear before the holiday selling stacks of cards from sidewalk stall. The Israel Postal Service would hire extra workers to help sort and deliver the ten million sacks of mail that piled up before the holiday. The cards also offered a form of anonymous folk art, said Sarfati. Graphic artists would create the cards, decorated with iconic images of Israel, creating a kind of “creative outlet on a wide spectrum of subjects,” she said. The cards were a method of expressing Israelis’ feelings “about everything,” she added, from joy over the creation of the state of Israel and belief in its leaders to statements of satire and caricatures of political leaders in later years. A Rosh Hashanah greeting featuring Elvis Presley in a photo from the 1960s, made in Israel in the 1970s (Courtesy Israel Museum) In the earlier years, there were images of the Israeli landscape, pioneering kibbutz farmers, and later, portraits of Madonna, Michael Jackson and Elvis. Cards from the early 1950s expressed wishes for proper housing for new immigrants or an earlier version of the selfie, with self-portraits of the well-wisher portrayed against the Western Wall or Tel Aviv beach. Now that email and social media reign, the annual greeting cards are often relegated to e-cards, and often don’t get sent at all, as people instead wish each other a happy new Year in a Facebook thread or with a selection of emojii in a Whatsapp text message. But whatever the method of communication, it’s the message that counts. Happy New Year. “Each Year Anew” opened on August 19 and is located in the library reading room of the museum. ebay3051